Summary Report

The Summary report in English was developed as the first Intellectual Output of the AGFSOSY project. The leader of the output was Hungarian organization Soproni Egyetem Kooperacios Kutatasi Kozpont Nonprofit Kft (SoEKKK).

This report was developed within WP1. The main objectives were to gather and analyse information about the current situation of agroforestry implementation both in the partners’ countries[ and in the rest of Europe, and to select a group of beneficiaries that will contribute to testing the training materials to be developed within the project. In this report, the authors summarised the available data included in the national reports about the current situation of agroforestry, as well as the results of surveys carried out among stakeholders in each country (farmers, researchers, advisers, multipliers etc.) which collected information on their views on the development, barriers and incentives, opportunities and expectations related to agroforestry. In order to gather all the required information and correct data from partners’ countries, a questionnaire and methodology specified for the project’s purposes had been developed. More than 30 interviews in six countries were prepared and carried out personally with the most relevant stakeholders during the survey. The results of the survey were integrated into the relevant sections of the report; therefore the document does not only serve as an up-to-date description of the status of agroforestry in the countries involved in the AGFOSY project, but also reflects the needs for future development from a practical approach with the contribution of the stakeholders.

Download PDF

- forms of shifting agriculture with fallow management i.e. combining agricultural crop cultivation with tree plantation in time;

- establishment of forest plantations in which annual crops are cultivated simultaneously, but only temporarily (for the first 1-3 years or until the foliage of the trees is fully developed).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In Wallonia, agroforestry practices are relatively limited. In Flanders, there are significantly more examples. This is partially because there has been a government subsidy for agroforestry. There are three types of agroforestry measures currently practiced in Belgium: a) “first generation agroforestry” (conservation and maintenance of hedges or isolated trees within an agricultural plot), b) “second-generation agroforestry” (implementation of woody plants in low density to a more conventional agricultural system with a view of profitability from production) and c) “third generation” or "multi-objective agroforestry" (implementation of woody plants in order to increase the resilience of the system by putting the "tree" at the centre of thinking).

ILVO estimates 2,000 ha in Flanders, and an unknown area in Wallonia (though they do note that 150 ha are in official programs). (ILVO, 2016.) In Belgium in the Wallonia region it was estimated that there was about 15,500 km of hedgerows and windbreaks (AGFORWARD). Ancestral agricultural practices, nowadays considered as agroforestry, can still be found in Belgium in the form of hedges and isolated trees. This form is probably the most common type of agroforestry. As far as second- and third-generation agroforestry is concerned, the enthusiasm remains limited and only a few farmers have implemented greater resources to achieve a more ambitious objective.

|

|

Agroforestry is nowadays a nearly forgotten phenomenon in the Czech Republic and there are no official data about the state of agroforestry. A research study calculated the total extent of agroforestry systems in the Czech Republic to be 35,750 ha in 2018, which is equivalent to 0.45 % of its territorial area and 0.8% of the utilised agricultural area (Lainka, 2018). In contrast, Herder et al. (2017) in their study found that agroforestry in the Czech Republic covered about 45,800 ha. According to Lainka (2018) the most common agroforestry practice seems to be livestock agroforestry that covers 30,031 ha, followed by grazed high value tree agroforestry which covers 5,720 ha. However, the study did not cover sequential agroforestry (rotational) systems, forest farming practices, home gardens, buffer strips, windbreaks, hedgerows, and shelterbelts that may cover thousands of hectares.

Agroforestry systems in the Czech Republic are currently represented mainly as relict forms of specific farming. The most extended traditional agroforestry practice is silvopastoral form of pasený sad (grazing of extensive fruit orchards) remaining in sites with less favourable conditions for intensive agriculture (e.g. mountains – regions of White Carpathians and Bohemian Forest) and linear tree planting or other tree elements (buffer strips, windbreaks, hedgerows and shelterbelts, etc.) on agricultural land. There are also other agroforestry systems such as intercropping of forest trees and forest farming/gardening. On the other hand, agroforestry is commonly practiced in gardens, for example by growing crops under fruit trees or in combination with domestic animals. A specific form of agroforestry systems in the Czech Republic is the cultivation of fast-growing trees on agricultural land intended for the production of biomass for energy use in combination with plant production, as well as livestock production (poultry, pigs, sheep, etc.).

|

|

Besides the remaining traditional systems (grazed orchards in Normandy, hedgerows systems in most of the livestock regions, silvopastoral practices in the mountains, etc.) there are newer systems being developed. Over the past thirty years, innovative practices have emerged, building on traditional knowledge, research, and grassroots experiences from pioneer farmers. These evolutions have occurred mainly in arable crops, poultry, viticulture, and market gardening.

Hedges and windbreaks (including riparian buffers), alley cropping associating cereals and nut trees and vegetable orchards are examples of agroforestry systems that are increasingly being rediscovered and adapted to the current constraints on the agricultural production (incl. mechanisation). Many "modern" agroforestry practices also seek to increase permanent soil coverage and encourage sustainable soil management practices. Agroforestry farmers are often engaging a more global transition towards agro-ecology, including conservation agriculture practices, minimum tillage, rotational grazing, and others.

|

|

Wood pastures including forest tree species and wild fruit trees are important landscape elements in Hungary. Additionally, grazed forests as part of the silvopastoral systems have always been an integral part of land use as demonstrated by a number of archived, historical sources and oral historical data. The economic and social value of such systems is hinted in the name “Glandifera Pannonia” (meaning ‘acorn bearing Pannonia’) to denominate Transdanubia in the Roman Age. The significance and operation of silvopastoral systems has reduced substantially in the past 100 years, and common ownership of pastures in forested areas has vanished almost entirely. Researchers estimate that there is currently only around 5,500 ha of used or abandoned wood pasture in Hungary, with a third in a protected area. In AGFORWARD, the coverage of woodlands and shrubland/grassland with sparse tree cover is estimated to exceed 36,000 ha. Although there is a significant interest in the benefits of agroforestry, there is a lack of basic knowledge about agroforestry practice and no information available about the number or total area of AF systems.

Nowadays, arable agroforestry – excluding windbreaks and shelterbelts – have almost disappeared from the Hungarian countryside. According to Frank and Takács (2012) the total area of shelterbelts in Hungary was about 16,000 ha at the beginning of the 21st century. In the latest years, because of the reduced deterioration in the quality and yields of some crops in affected areas due to the effects of climate change several pilot projects started to investigate the possibilities for climate-adaptive arable crop production in agroforestry systems in Hungary. In addition, other agroforestry systems such as intercropping in forest plantations and short rotation coppices combined with livestock can be found sporadically.

Similarly to the northern neighbouring countries, agroforestry is commonly practiced in homegardens, in a form of mixed systems with crops, fruit trees and/or domestic animals. There is no recent data available on other arable agroforestry systems such as alley cropping, riparian buffers, or forest gardens, some of which are considered as new (atypical or not applied so far) land use technologies in Hungary. Recently these silvoarable systems have been established on a small scale mostly as pilot systems for educational and/or experimental purposes.

|

|

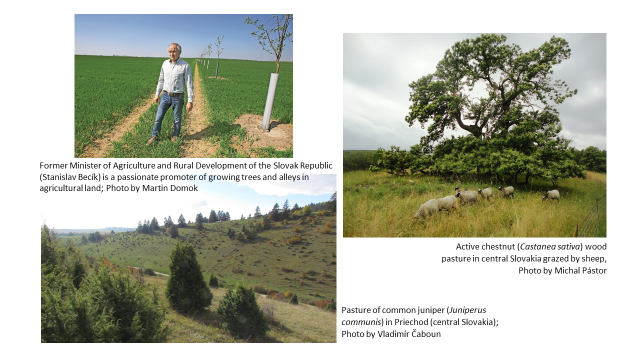

There are no official data about the state of agroforestry in Slovakia. Agroforestry is nowadays a “brand new” topic for both researchers and farmers. According to Špulerová et al. (2011), current area of traditional agricultural landscapes in Slovakia is less than 1 %. In AGFORWARD, the total extent of agroforestry systems in Slovakia was calculated to be about 43,900 ha (Herder et al., 2017), which is equivalent to 0.6 % of its territorial area. They also present that the most common agroforestry practice seems to be livestock agroforestry that covers 41,900 ha, followed by grazed high value tree agroforestry which covers 2,000 ha. Slovakia has a long tradition of pastoralism and sheep breeding, with favourable natural conditions for these activities. Therefore, probably the most extended traditional agroforestry practice is silvopastoral form (extensive pasture on grasslands/meadows and grazing of extensive high-trunk fruit orchards) remaining in sites with less beneficial conditions for intensive agriculture (e.g. mountains – regions of White Carpathians) and linear tree planting or other woody elements (riparian buffer strips, windbreaks, hedgerows, etc.) on agricultural land.

Often, agroforestry practice in Slovak rural areas is commonly practiced in gardens (kitchen gardens or homegardens), for example by growing crops under different tree species or in combination with domestic animals. In recent time, in Slovakia there has been a “big boom” of fast-growing trees (Paulownia spp., Salix spp., Populus spp., Juglans nigra etc.) on agricultural land preferentially intended for the production biomass for energy, but also for firewood and edible nuts and often in combination with plant production (vegetable, cereal etc.).

|

|

A large abundance of agroforestry areas can be found in the south-western, central and northern parts of Spain. The total estimated AF area (high value tree + livestock + arable agroforestry systems) is approximately 5,584,400 ha, which represents 23.5% of the Spanish UAA (Herder et al. 2017). According to another estimation, only about 5.2% of the cultivated land has agroforestry systems and only 4.9% of the arable crops are carried out in plots with trees (Lumbreras, 2011).

One of the most representative agroforestry systems is the Dehesa with an estimated area of 3.5 million ha in the five Autonomous Communities where these formations appear[1]. Of this area, Extremadura has almost 1,250,000 ha (35%), Andalusia with almost 1,000,000 ha (27%), Castilla La Mancha with 750,000 ha (21%), Castilla y León with 500,000 ha (13%) and Madrid with less than 100,000 ha (3%).

[1] Diagnosis of Mediterranean Iberian dehesas (MAPA 2008)

[1] Diagnosis of Mediterranean Iberian dehesas (MAPA 2008) |

- producing food for humans and animals

- producing wood-timber for building, furniture in housing, and boats

- producing wood poles for fencing and plot limits

- source of energy (firewood, charcoal)

- Environmental: integrating woody vegetation into a production system offers many benefits to the ecosystem, both for the soil and for biodiversity. The installation of woody plants in or near crops and pastures creates habitats for associated flora and fauna and thus enhances biodiversity both above and below ground, but also provides shelter for domestic animals during bad weather or extreme heat. Trees not only prevent water and wind erosion by favouring water infiltration and providing vegetation cover, but also improve soil structure by the roots and the return of organic matter to the soil (through the decomposition of leaves and roots or use of its remains for composting). The organic matter content is increased and thus soil fertility and conditions for the edaphic fauna are improved. In addition, this technique offers a partial solution to the oversupply of chemical inputs applied by the farmer through roots that draw their resources from deeper soil layers. This limits the leaching of these inputs into groundwater along with optimization of the use of nutrient resources. Finally, trees greatly contribute to balancing climatic extremes and their impacts by creating a specific microclimate (mitigation in terms of light, wind, temperature etc.), thus supporting the so-called small water cycle and increasing system resilience to climate change. These aspects are particularly relevant in areas with strong winds, as trees soften their intense drying effect. Besides this, agroforestry is considered climate regulatory service due to CO2 capture into long-term carbon sink (in form of wood).

- Economic: preserving or increasing total production according to the Land Equivalent Ratio (LER) principle; greater production security, multifunctional farming and distribution of risk of farming, providing pasture/fodder to animals, human food, inedible materials including firewood, sap, resins, tannins, insecticides and medicinal compounds, and high-quality products. Trees help to improve the bottom elements of the agro-ecosystem (e.g. through shading). Linear AF systems (e.g. windbreaks, hedges) protect the production systems. Beneficial effect on the population of pollinators (new habitats) play a crucial role both economically and environmentally. Economically, it can increase yields as well as provide additional revenue streams, thus increasing profits for farmers and landowners due to additional sales of crops and side commodities. Intermediate incomes can be expected if fruit species have been planted, as well as through the production of firewood, basketry etc.

- Social and cultural: AF brings forth an increase of employment in the countryside (more manpower is needed per unit area), and with it the stabilization of the rural population. It supports selfsufficient family farming and intergenerational exchange in the farm management. Traditional agroforestry practices promote cultural traditions and habits, bring back local food and heritage varieties and maintain popular knowledge linked to the production system and its elements. In this way, AF improves the relationship of the population to the landscape. Furthermore, it can play an important role at territorial and landscape levels, as it also offers new landscapes, which adds value to ecosystem services for recreation but also contributes to improving health and well-being of both rural and urban communities. Agroforestry offers a positive image of agriculture, which is an asset from a societal point of view.

- reluctance to switch to agroforestry for fear of reducing agronomic and financial performance of the farm and strong social pressure to continue farming as industrial agriculture sets;

- trees are perceived as an obstacle to modernization, as it is more difficult for large machines to pass through the land

- economic and environmental benefits are perceived in long term as compared to annual cropping

- elimination of trees, hedges and alignments structuring the landscape to expand the cultivated plots and facilitate mechanization

- agroforestry systems are complex, labour-intensive and demand additional skills and knowledge

- low economic interest in production of firewood, due to cheap fossil fuels

- financial expenditure and mobilisation of human resources can be substantial, while the financial benefits will only come to the valuation of the wood products, in the medium and long term

- planting trees out of forest is complicated due to the lack of concept of agroforestry in the national law

- lack of information about methods of agroforestry farming (e.g. on plant combinations or protection of seedlings in combination with grazing animals) and lack of proper technical advice available to farmers (especially tree monitoring/management)

- lack of decisive support from public administrations prevents farmers to continue or start a new activity

- lack of information on economic references

- complexity of administration associated with the introduction of agroforestry.

According to the interviewees, the lack of knowledge, practical examples, and the attitudinal deficiencies are the main constraints. Some of the interviewees think that the main barrier is not the lack of expertise, but of the intent and that, the support system is not capable of disrupting it. According to the respondents, study tours, online training materials, and complex adult training programmes can help farmers the most in the first implementation and management of AF systems. The larger part of the stakeholders are aware of the training and educational programmes, but most of them are busy with their farm and cannot afford it.

According to the interviewees, the lack of knowledge, practical examples, and the attitudinal deficiencies are the main constraints. Some of the interviewees think that the main barrier is not the lack of expertise, but of the intent and that, the support system is not capable of disrupting it. According to the respondents, study tours, online training materials, and complex adult training programmes can help farmers the most in the first implementation and management of AF systems. The larger part of the stakeholders are aware of the training and educational programmes, but most of them are busy with their farm and cannot afford it.

- creation of scientific background for agroforestry systems (evaluation of potentials, monitoring of ecosystem services, developing decision support system);

- development of decision-support tools, models and tools focused on innovations for farmers in favour of agroforestry systems and mixed farming systems;

- encouraging exchange and transfer of knowledge between scientists and agroforestry practitioners, putting research results into practice and promoting innovative ideas to address the challenges and solve the problems of practitioners;

- expanding the current AF networks to ensure actual adoption of innovative agroforestry practices;

- evaluation of the benefits and constraints of using agroforestry systems with a focus on the socioeconomic, legal and environmental context.

| Country | Closed until 2019 | Ongoing or planned |

| Belgium | I: AGFORWARD (AGroFORestry that Will Advance Rural Development I: AGROFE (Transfer of agroforestry knowledge by transforming research results into pedagogical material) | I: AFINET (AgroForestry Innovation NETworks) N: ‘Agroforestry Vlaanderen’ (“Agroforestry in Flanders”) (2014 – 2019) I: INTERREG “Forêt Pro Bos” I: INTERREG “AForCLIM” New project specific to hedge management starting in 2019 |

| Czech Republic | M: AGROFE (Transfer of agroforestry knowledge by transforming research results into pedagogical material) | N: “Agroforestry - potential for regional development and sustainable rural landscape” N: Agroforestry systems for conservation and rejuvenation of landscape functions threatened by climate change |

| France | M: AGFORWARD (AGroFORestry that Will Advance Rural Development – agrolesnictví pro venkovský rozvoj) N: Ecosfix (ekosystémové služby kořenů stromů v agrolesnických systémech) N: Casdar Smart (zeleninové sady), Casdar Arbèle (přežvýkavci) Casdar Vitiforest N: Réseau Rural Agroforestier (venkovská síť) M: AgroFE M: AGROF-MM | I: AFINET (AgroForestry Innovation NETworks) N: Agr’eau Adour Garonne (regional programme supporting AF development at landscape level) N: Bouquet project on the AF chicken N: MycoAgra project (impact of AF on soil biota) N: RMT I: Poplar AF |

| Hungary | I: AGROFE (Transfer of agroforestry knowledge by transforming research results into pedagogical material) I: AGFORWARD (AGroFORestry that Will Advance Rural Development I: AgrofMM – Training in agroforestry | I: AFINET (AgroForestry Innovation NETworks) N: Széchenyi 2020 EFOP-3.6.2-16 - Grow together with nature – agroforestry as a new breakout opportunity N: Széchenyi 2020 EFOP-3.6.2-16 - Sustainable raw material management thematic network development - RING 2017 |

| Slovakia | N: "Agroforestry systems for combined production and more efficient use of agricultural land" (planned) I: SMARTFARM (Smart Farming: Fostering Mixed Farming) Systems and Agroforestry (planned) | |

| Spain | I: AGFORWARD (AGroFORestry that Will Advance Rural Development) | I: AFINET (AgroForestry Innovation NETworks) N: Life11 BIO/ES/000726 Dehesa Ecosystems: development of policies and tools for the management and conservation of biodiversity |

Recently, agroforestry is present at different levels in the education of the countries involved in AGFOSY. European Agroforestry Federation (including all the countries below) is also a significant party in training programs for agroforestry.

Recently, agroforestry is present at different levels in the education of the countries involved in AGFOSY. European Agroforestry Federation (including all the countries below) is also a significant party in training programs for agroforestry.

Generally speaking, while there is a positive trend in higher education, there is hardly any information on agroforestry appearing in high or secondary schools. Thus, agroforestry training of technicians and experts close to the practice would be of high importance.

Among the improvement opportunities for the implementation of agroforestry, we can highlight the strengthening and promotion of formal and non-formal training in agroforestry, adapted to all kinds of audiences, from researchers to farmers, which would democratise knowledge. For example, by the transfer of knowledge from research centres to the field through medium and long-term programmes that guarantee its sustainability and durability. Therefore, public investment in research programmes is inevitable to achieve further progress in the field of knowledge and innovations that help decision-making.

Generally speaking, while there is a positive trend in higher education, there is hardly any information on agroforestry appearing in high or secondary schools. Thus, agroforestry training of technicians and experts close to the practice would be of high importance.

Among the improvement opportunities for the implementation of agroforestry, we can highlight the strengthening and promotion of formal and non-formal training in agroforestry, adapted to all kinds of audiences, from researchers to farmers, which would democratise knowledge. For example, by the transfer of knowledge from research centres to the field through medium and long-term programmes that guarantee its sustainability and durability. Therefore, public investment in research programmes is inevitable to achieve further progress in the field of knowledge and innovations that help decision-making.  During the 2007-2013 period, Hungary was the only country in Central Europe that implemented the EU Measure 222 (First Establishment of Agroforestry on Agricultural Land) which opened the eligibility period lasting for 6 years from 2009. For the 2014-2020 period, the conditions of support have changed, but the number of options for implementation of AFS increased by extending the support beyond the implementation of wood pastures to shelterbelts and AF innovations through the creation of operational groups. In Spain, specific programs such as the Master Plan for the Andalusian Dehesa as well as those aimed at improving production linked to Dehesa and the processing industries for their products provide significant support for agroforestry. Further funding is available for other related activities such as diversification of uses, integrated planning or improvement of basic services, infrastructure and equipment. Moreover, national projects and materials focusing on the conservation and integral management of Dehesa as well as the development of Law 7/2010 for Dehesa through the promotion of the main management instruments provided therein. Other agroforestry systems such as family orchards or live fences lack institutional support for their survival.

The institutional support of agroforestry in France is ensured by:

During the 2007-2013 period, Hungary was the only country in Central Europe that implemented the EU Measure 222 (First Establishment of Agroforestry on Agricultural Land) which opened the eligibility period lasting for 6 years from 2009. For the 2014-2020 period, the conditions of support have changed, but the number of options for implementation of AFS increased by extending the support beyond the implementation of wood pastures to shelterbelts and AF innovations through the creation of operational groups. In Spain, specific programs such as the Master Plan for the Andalusian Dehesa as well as those aimed at improving production linked to Dehesa and the processing industries for their products provide significant support for agroforestry. Further funding is available for other related activities such as diversification of uses, integrated planning or improvement of basic services, infrastructure and equipment. Moreover, national projects and materials focusing on the conservation and integral management of Dehesa as well as the development of Law 7/2010 for Dehesa through the promotion of the main management instruments provided therein. Other agroforestry systems such as family orchards or live fences lack institutional support for their survival.

The institutional support of agroforestry in France is ensured by:

- The implementation of measure 8.2 of the CAP (Pillar 2) in about 30% of the regions;

- Regional/local policies and programmes (including funding for planting and R&D activities);

- Natural resource management and landscape planning frameworks promoting agroforestry implementation and knowledge transfer;

- A national plan for agroforestry (2015-20)4 set as a national strategy to enhance the visibility of agroforestry on the political agenda.

| Country | English name of AF civil organisation | Year of foundation |

|

Association pour la Agroforesterie en Wallonie et á Bruxelles (AWAF) | 2012 |

|

Český spolek pro agrolesnictví/Czech Association for Agroforestry (CSAL) | 2014 |

|

Association Française d’Agroforesterie (AFAF) Association Française Arbres Champêtres et Agroforesteries (AFAC) | 2007 2007 |

|

Agroerdészeti Civil Társaság/Hungarian Agroforestry Civil Association (ACT | 2014 |

|

Slovak Agroforestry Association (SALS) | under preparation |

|

Asociación Agroforestal Espanola/Spanish Agroforestry Association (AGFE) | 2016 |

Due to economic realities, farmers tend to focus on short term solutions. This is often due to the farmer not being the owner of the land they are farming. As a result, they do not consider agroforestry economically viable because the long-term advantages of agroforestry does not have such a big impact for them. Farmers are often concerned about losing cropland to trees however, proper selection of tree species and careful planning, planting and management can significantly increase the total productivity of the entire production system. In addition, ecosystem services are important components of return, but mostly they are not valuable in the short term. Thus, more information should be provided to practitioners about the financial benefits of agroforestry. In order to strengthen the marketing of AF products and running profitable farms, the creation of public product processing centres (coordinating logistics, marketing and distribution channels) should be supported to obtain greater added value and encouragement for producers to sell their products through short channels. Agroforestry does not work without long-term land availability, therefore, facilitating access to land is crucial, for example by the creation of "land banks" aimed especially at rural women and young people. In this way, strengthening the transfer of agroforestry traditions and knowledge between generations could also be promoted.

Due to economic realities, farmers tend to focus on short term solutions. This is often due to the farmer not being the owner of the land they are farming. As a result, they do not consider agroforestry economically viable because the long-term advantages of agroforestry does not have such a big impact for them. Farmers are often concerned about losing cropland to trees however, proper selection of tree species and careful planning, planting and management can significantly increase the total productivity of the entire production system. In addition, ecosystem services are important components of return, but mostly they are not valuable in the short term. Thus, more information should be provided to practitioners about the financial benefits of agroforestry. In order to strengthen the marketing of AF products and running profitable farms, the creation of public product processing centres (coordinating logistics, marketing and distribution channels) should be supported to obtain greater added value and encouragement for producers to sell their products through short channels. Agroforestry does not work without long-term land availability, therefore, facilitating access to land is crucial, for example by the creation of "land banks" aimed especially at rural women and young people. In this way, strengthening the transfer of agroforestry traditions and knowledge between generations could also be promoted.